Biography

Zhang Hongtu was born in 1943 into a Muslim family in china in Pingliang, Gansu Province, which is 100 miles northwest of Xi’an. After moving from the North to the South of China, he settled in Beijing with his parents in 1950. His father was a scholar in China, and his mother came from a business family. During high school, at the school attached to the Central Academy of Fine Arts, he learned different artistic techniques, which eventually hit his heart and led him to become an artist.

During his youth, he notes that he learned that Mao Tse Dong and the Long Walk were not truthful and that the people of China were living in a lie, as he states on his momao.com website; “In the same way, when I lived in China, I saw the positive image of Mao so many times that my mind now holds a negative image of Mao. In my art, I am transferring this psychological feeling to a physical object” In fact, people were dying under the government’s regime and felt lied to. Hongtu eventually felt he wanted to leave China for the United States. His artwork was greatly influenced by what he experienced during this time.

During the ’80s and ’90s, Hongtu found it was difficult for him to fit into society for several reasons stated in an interview; “Traditionally Chinese intellectuals and artists have kept a kind of distance from their reality. I mean that they haven’t dealt directly with social and political problems in their art. But coming here allowed me to have a different approach. I feel isolated from my new reality here, perhaps because of the language problems, lifestyle differences, and cultural shock. I can fit in, but I still feel different. When I show the head surrounded by space, it shows that isolation”. He mostly used newspapers as a form of art. His main goal was to forget everything by coming to America. For Hongtu, he notes that the place he called home was in New York. During this early period in the US, Hongtu continued to learn more about the truth of his old home in China. He wanted to express what he knew and felt through his artwork during this time in the United States

His transition from China to the United States in 1982 became central to his work. For example, some pieces that the artist produced during this time were his works Quaker Oats 1989, Last Banquet 1989, and Unity and discord. Quaker Oats became the blueprint for the political pop movement that he was a part of that helped showcase contemporary Chinese Paintings. This piece helped show off his ideas on how Mao was the face of China, which is stated in an interview; “I felt nervous and guilty while I was cutting Mao’s images for a collage. It would jeopardize my career if I did that in China, as some of my Chinese friends had pointed out. This kind of guilty feeling became a motivation for me. I thought about it some more. Why am I able to use Bush’s and Clinton’s images freely but not Mao’s, even though Mao has already been deceased for many years? I felt that it was my psychological barrier. To the Chinese of my generation, Mao’s image was very special. However, to Andy Warhol (1928-1987), Mao’s image was no different from Campbell soup’s and Marilyn Monroe’s. My Mao series ended when my guilty feeling was gone, and Mao ceased to have power over me.” The Tiananmen Square protest further inspired his work, including creating the Last Banquet and Red Door.

Hongtu often used the image of Mao in his work. For the artist, China’s nightmare was Mao being at your door, as shown in his work (Front door art 1995).

In 2006, Hongtu was featured in the documentary “Yellow Ox Mountain.” In 2015, Hongtu was invited to Deichtorhallen in Picasso’s Art Museum. He was also in the exhibition a “Brief History of Human Kind” in the Israel Museum. His later and more current work has a new aspect of a vision of the themes in the environment and climate change.

In 2018, he visited Kansas, and this was the start that inspired him to start to work on his Bison pieces and concentrate on nature themes.

Art Practice and Art Work

Zhang Hongtu’s art style comes directly from his experiences in China. After emigrating, he credits his new home in the United States as inspiration to his artwork. His Chinese background has affected much of his career. He has said that being Chinese and the Chinese culture has become a part of his life. Therefore his art reflects that—his artwork shifts from categorically political to others that altogether avoid politics. Politics is part of his background; that is why Mao is his inspiration. Zhang Hongtu’s art also deals with cultural and social issues. Though this is the case, he does not like to think of his work as strictly political or not.

Zhang Hongtu’s non-political work is easier to understand, especially for those unfamiliar with his personal experiences. His work being contemporary can be a bit controversial. Even though his Chinese background and Chinese culture play a substantial role in his art, he uses his new life in New York as inspiration. Seeing his earlier work, he incorporated Western contemporary and Chinese traditional and merged them. The Chinese culture has always followed a standard form of art. The idea of censoring some artwork, and when Zhang Hongtu lived in China, he recalls only learning about Socialist Realism art.

He uses satire and parodies in his artwork, in both his political and non-political pieces such as the below, and incorporates his experiences living in the East and West.

Photo collage and acrylic on paper

9.5 X 11 inch

1989

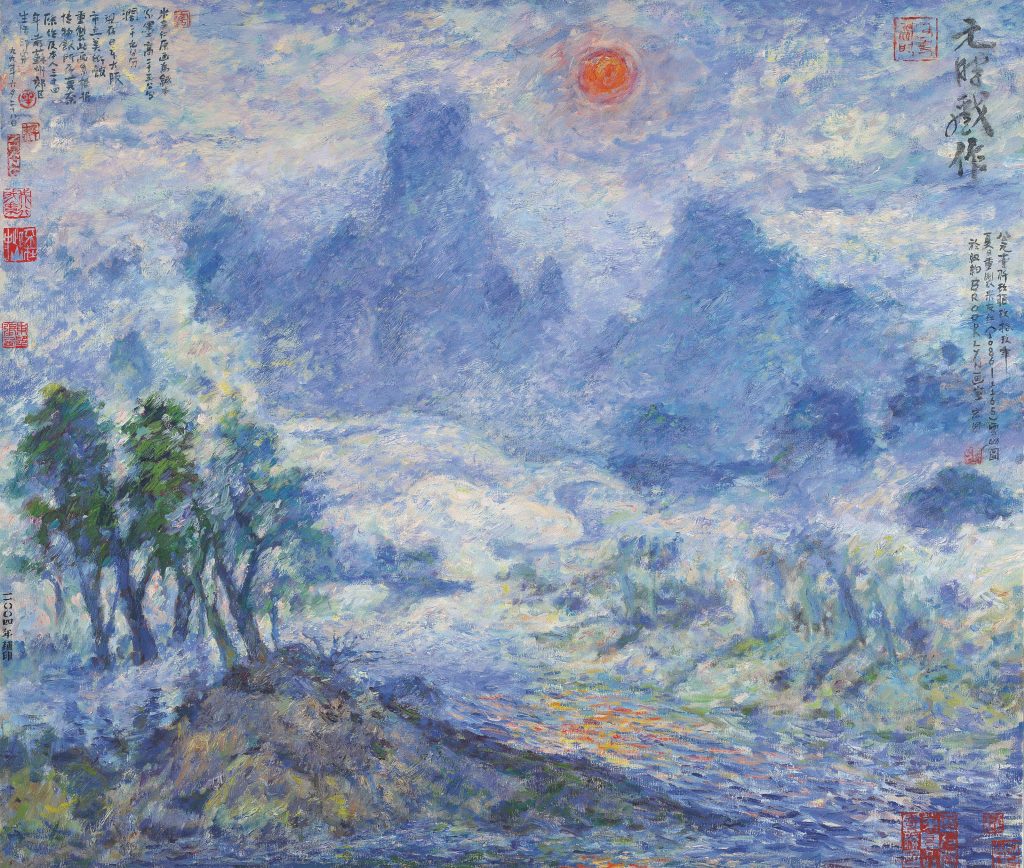

Oil on canvas

78 X 22 inch

2000

We can also see his work differ from his paintings before he moved to New York. The transition seen demonstrates how his artwork no longer has boundaries.

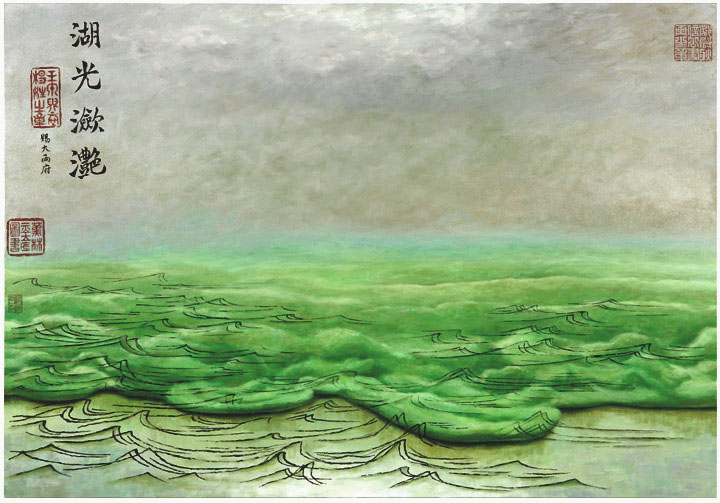

Watercolor on paper

7 X 7.7 inch

1963

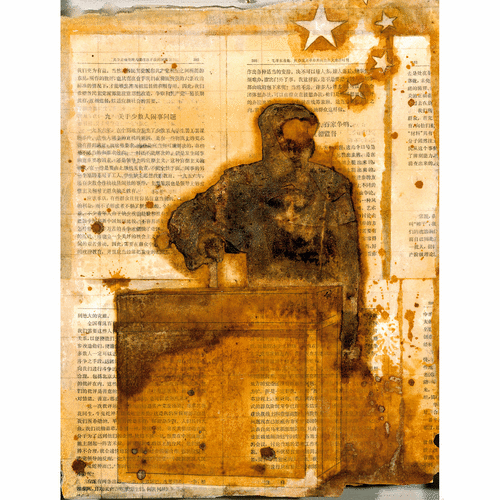

Ink and acrylic on newspaper

43 x 27 inch

1984

Zhang Hongtu’s exhibits demonstrate a great deal of who he is as a Chinese immigrant. His childhood experiences with art being filled with a copy and paste method in which everyone’s work was indistinguishable. New York, on the other hand, was the complete opposite artistically at the time. As time went on, his art also grew. The sophistication in his work allowed him to create abstract pieces that portrayed himself.

Porcelain

Actual size

2002

Many have expressed Zhang Hongtu’s artwork to have “blurred boundaries” as he shifts from different art styles and cultures. This ultimately defines Zhang Hongtu as an artist. From the start of his journey as a Chinese artist living through a Cultural Revolution to then incorporating his Chinese background into Western art styles, he later merged all of his art styles to create a representation of who he is.

Oil on canvas

64 x 32 inch

1998

Art Style and Work

Zhang Hongtu’s work is very diverse, and his art style is multi-faceted. From oil paintings that can cover an entire wall to small ceramic sculptures when compared. He is mainly known for his work on Mao, but his oil paintings are also a marvel to look at. Zhang Hongtu uses the style of traditional oil paintings and adds his modern new twist to it each of his work. Instead of using regular or oil paint, he sometimes used soy sauce as a substitute to show his background and heritage; this is only to show his style, which goes against the grain and is very vocal.

111 x 131 cm

1999

48 x 30 cm

1993

Moving away from the canvas, Zhang Hongtu also is famous for creating sculptures and ceramics which is a stark contrast to oil paintings and is a completely different art format. This just goes to show how versatile Zhang Hongtu’s art style really is.

29.2 cm

2002

274.3 x 152.4 x 76.2 cm

1995

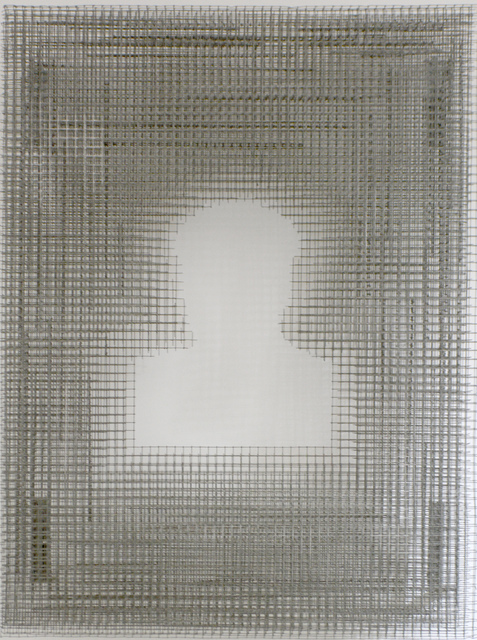

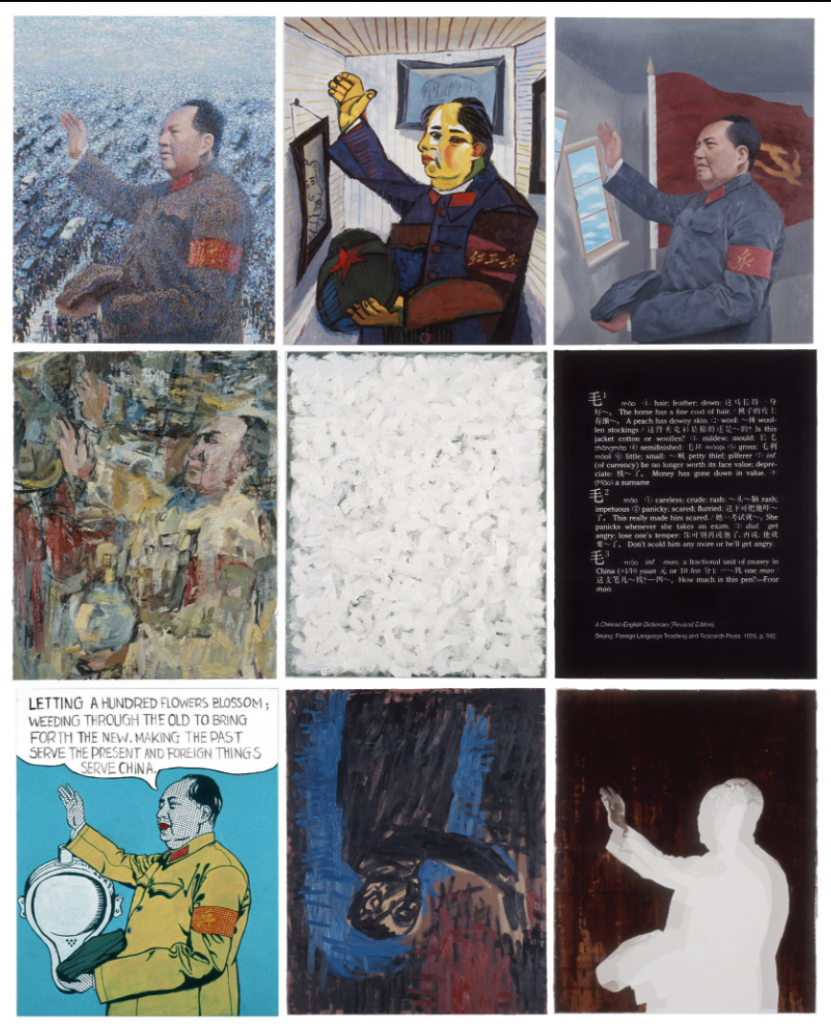

In his Material Mao series, Zhang Hongtu uses many different objects to create the same outline of Mao. These objects are a glimpse of the past and into Mao’s undesirable legacy. Wire mesh, corn, rice, soil were just some of the things he uses for his art and to spread his message.

99 cm

1992

99 cm

1999

All in all, one thing is clear and that is, his art never fails to address the the specific issue that concerns him during the time.

Gallery

Oil on Canvas

50″ x 72″

2008

Earthenware with sancai glaze

Actual Size

2002

Oil on Canvas

94x38x 1 5/8 in.

2002-03

Zhang Hongtu, Quater Oats, (date, format, medium, collection)

Zhang Hongtu, The Nightmare of Mao At Your Door In China, date format, collection (perhaps put this at the top where it is referend?)

Timeline

1943- Birth of Zhang Hongtu. Born in Pingliang, Gansu Province, China. Hongtu was born into a traditional Muslim family.

1960 through 1964- Zhang Hongtu attended high school attached to Beijing’s prestigious Central Academy of Fine Arts where he learned basic painting techniques.

1964- Central Academy of Fine Arts was no longer accepting students (The Academy was described as “corrupt” by Mao’s wife). Instead, Zhang Hongtu began his professional art studies at Beijing’s Central Academy of Arts and Crafts.

1966- Outbreak of the Cultural Revolution. Mao launched the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

1972- Zhang Hongtu married Huang Miaoling (a ceramist at the Arts and Craft Academy).

1973- Zhang Hongtu assigned to work with Beijing Jewelry Import-Export Company, where he designed jewelry for about 9 years.

1979 through 1981- The Jewelry company allowed for him to leave and go to New York to study at Art Students League although originally they were against it. Zhang Hongtu joined an unofficial art group, Tongdai Ren (politically and artistically bold move to make at the time in China).

1982- Zhang Hongtu arrives in the United States.

1982 through 1984- Zhang Hongtu worked in construction (painting walls, cutting stone, and mats for a fine arts framing company).

1984- Sold two of his paintings (second painting sold to the World Bank in Washington, D.C for $1,800).

1987- Quaker Oats Box (this became the blueprint for the “political pop” movement that helped showcase contemporary Chinese painting).

1989- Last Banquet (satirized communist Mao Zedong and his ideological scriptures) as well as his Chairman Mao series (twelve works).

1991 through 1993- Material Mao series created.

1994- Last Banquet originally priced at $4,000 sold for $50,000 (Zhang Hongtu decided to quit working in construction and become a full time Chinese artist in America).

1995– Collaborated with a fashion designer named Vivienne Tam, her provocative designs of Mao caused tension and controversy in the United States and China.

1997- Unity and Discord series.

2002- The Last Banquet was shown at the Paris Peking exhibition.

2006- He was featured in a documentary film “Yellow Ox Mountain” directed by Miao Wang.

2009- He participated in the grand opening exhibition at Tina Keng Gallery, Taipei, Taiwan. In October his mother passed away.

2015- Hongtu was invited to Deichtorhallen’s Picasso in Contemporary Art in Hamburg, he was also in Whyte Museum’s exhibition Water, and Israel Museum’s exhibition A Brief History of Humankind. Also exhibited solo in Queens Museum, New York, U.S.A. The Journey Begins -Zhang Hongtu 1985‐2004, Tina Keng Gallery, Taipei, Taiwan.

China: Through the Looking Glass, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, U.S.A.

After Picasso: 80 Contemporary Artists, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio, U.S.A.

Wild Noise: Artwork from the Bronx Museum, El Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Havana, Cuba.

Picasso in Contemporary Art, Deichtorhallen, Hamburg, Germany.

2016- A Brief History of Humankind, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

A Brief History of Humankind, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn, Germany.

2017- Two Rocks: Nobuo Sekine and Zhang Hongtu, Baahng gallery, New York, NY, U.S.A.

Uncharted Waters, Boers-Li gallery, New York, NY, U.S.A.

Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY, U.S.A.

Self-Reimagined, Visual Arts Gallery, New Jersey City University, Jersey City, NJ, U.S.A.

Embrace or Rebel? Traditional Asian Art Techniques in Contemporary Practice, Amelie A. Wallace Gallery, SUNY College at Old Westbury, NY, U.S.A.

2018– Culture Mixmaster Zhang Hongtu, Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University, Zhang Hongtu: Van Gogh/Bodhidharma, Tina Keng Gallery, Taipei, Taiwan.

Zhang Hongtu: Van Gogh/Bodhidharma, Charles E. Shain Library, Connecticut College, U.S.A.

Chinese Medicine in America: Converging Ideas, People and Practices, Museum of Chinese in America, New York, U.S.A.

Blurred Boundaries, New York School of Interior Design art gallery, U.S.A.

2019- Zhang Hongtu: I Dare To Mate A Horse With An Ox, Baahng Gallery, New York.

Citations

Zhang Hongtu: The Art of Straddling Boundaries. Taipei and Beijing: Lin and Keng

Gallery, 2007. (Principal essay, “Zhang Hongtu: The Art of Straddling

Boundaries,” vii-xxv.)

Shaw, Dan. “Zhang Hongtu’s Art Studio in Woodside, Queens.” The New York Times. The New York Times, November 6, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/08/realestate/zhang-hongtusart-studio-in-woodside-queens.html.

Ge, Pan. “Q. And A.: The Artist Zhang Hongtu on Appropriating Mao’s Image,” March 21, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/22/world/asia/zhang-hongtu-artist-mao-china.html.